Issue #8

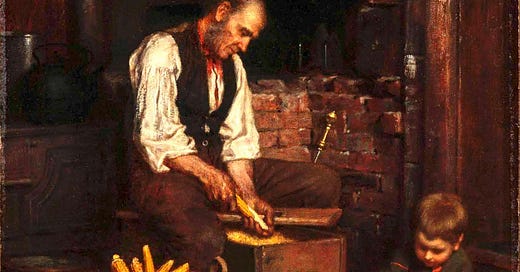

Corn-shelling, Eastman Johnson, 1864.

I

His mother died giving birth four short years ago. He is the last gift that she gave me. A child or our old age— unexpected, unwanted, but greatly loved. She was forty when she found she was pregnant. She had given birth to eight other children and had no desire for more. Three had been born dead— all boys—taken from us by the hand of Gabriel. She never complained. Never cursed God. Never raised her fist in anger like me. But I felt her spirit slowly being crushed like corn being ground into meal. Two of our children died in the year of the pox. All five lay buried on the hill where she lies, waiting for the return of our Lord and Savior. So his birth was a miracle— a gift from God. I named him Jeremiah for the great prophet of Israel, child of my loins, son of my flesh. May God have mercy on my soul. He has given new life to these tired bones, brought happiness to this weary soul, saved me from an existence of melancholy and despair. But like all things— God giveth and God taketh away. I miss my Sarah. How she winked at me when she laughed as if she was letting me in on some private joke. The compassion in her heart for the needy and less fortunate. Like when she plodded through a foot of freshly fallen snow to take food to the Yoders when their mother was sick. The mashed potatoes and gravy that she prepared with love. And the warm cornbread dipped in butter and honey. Watching him playing on the floor reminds me of her. He has her blue eyes, her quickness to laugh, her joy in small things. I am proud of him as only a father can be proud. The good book sayeth that pride goeth before a fall, and God knows, I've stumbled a lot in my life, but I can't help myself. Yes, I love his three older sisters but there is something special about him. Sarah gave me the son that I've always wanted— the last act of her love. Farming is hard work— even now shelling corn. I am reminded of the toil, the labor it took to raise this corn. But it is all worthwhile because I know one day the farm will be his if he wants it. The girls will leave me to live with their husbands and to raise their own families. That has always been God's way since the time of Adam and Eve. I hope that God will allow me to live long enough to see him work the fields. These bones of mine are weary—and full of aches and pains. Each day, I struggle to climb out of bed. Each night, I rub liniment on my tired muscles. He has the energy and vitality of my youth. If only I could experience what he sees. To understand what goes on inside his head. Neither of us talks much. I have never told him that I loved him. I've never told my daughters, either. But they are in my heart and thoughts. Soon, I must go outside into the harsh, cold winter night to milk our few cows and slop the hogs. But I linger, shelling the corn, watching him, remembering her. He loves to play with the corn cobs. He invents all kinds of games and stories in his small head. For awhile, he takes pleasure in building us a new cabin or maybe a barn. Then, magically, the cabin is transformed into a fort. I love to watch the way his mind works, sees things in new ways. May God be kind to him and not make him suffer as his mother and I have suffered. May he find joy and happiness in the simple things like shelling corn. I offer him—the only thing a father has to give—my blessing and my prayers. Praise be to God.

Notes

I wrote this poem in 2001 as part of an art history class. The painting is located at the Toledo Art Museum. The poem has three parts and is told from the father's point of view. This was the first poem that I ever wrote in response to a painting. The poem is one of my longest ones; you can read it in one sitting or multiple sittings.

II

The life of a farmer has not been easy. I came to this country when I was a mere boy. My father, an honest man seeking the freedom to worship God as he wanted, uprooted our family from the German soil and took us across the vast ocean. The trip was hard. There were days I thought I was going to die. I was often too sick to eat. Shortly before we landed in America, my younger brother caught the fever and died. And my mother never recovered from the pain of her loss. She blamed my father and denied him the joys of the marriage bed. She never took to this land with its strange people and even stranger customs. The harsh life of clearing the fields and tilling the soil did not suit her. She died a few years after we settled in Pennsylvania. I think about her often—even more as the years pass. My father uprooted us again and moved on to Ohio. I think he wanted to forget. He blamed himself for her death and that of his son. When I turned eighteen, I wanted adventure. I heard there was great farmland to be claimed on the prairie. I took off on my own and finally settled on a farm in central Illinois. A small conclave of the brethren took me in and made me feel at home. That is where I met Sarah and fell head over heels in love. She was my angel, fallen from the sky, sent by God to save my wretched soul, to teach me the lesson of love and to free me from the loneliness. I was smitten by her beauty, her long brown hair hanging to her waist, those deep blue eyes, a reminder of the ocean I had crossed a child. She was the oldest daughter of Peter Schertz, a Bible-thumping preacher, a devout Christian if God ever made one. Sarah was headstrong and full of mischief and said to have her father wrapped around her little finger. I first saw her in church, sitting in the front pew with her mother and sisters. I could only see the back of her head, the long brown hair. But I was hooked like a catfish on the worm. I was a shy young man in those days, and it took months to work up the courage to talk to her. She was a friendly girl who talked to everybody and everyone and even said hello to shy old me. But she moved on to the next person before I could stammer out my response. From early childhood, I have been a stutterer. For some reason, my brain and my mouth never connected. I knew what I wanted to say, but my mouth could not make it happen. I dreamed of her day and night as I tended to the needs of my farm. I desired to hold her in my arms, to tell her that I loved her, that she was everything I wanted in a woman. And in my dreams, she always told me she loved me too. My chance came at a picnic for the young people in church. I found myself alone with her, and I struggled to say something. When the words came out, they came in starts and stops. She waited patiently and did not laugh. She smiled words of encouragement, and asked me questions about myself. Slowly the words came to me, and I shared with her my hopes and dreams. She listened and seemed to understand and appreciate me for who I was. One thing led to another, and soon, I was courting her with all my heart and soul. I still remember the bundling— lying next to her in bed with her family in the next room. Some people outside the church believe bundling to be a strange and quaint custom of the brethren, but it served its purpose. It gave Sarah and me a chance to be alone during the cold of winter and yet protect her honor and virginity. And then came the marriage. Just her family and the congregation. My family could not make the trip from Ohio. Her father conducted the ceremony. I still remember the day—August 18, 1839— a hot, humid summer day. I rose at dawn to milk the cows, gather the eggs, and slop the hogs. Some of the ladies from church had come over the day before to clean, scrub, and decorate it. They even sewed curtains for the windows. I had never had curtains before. I usually dress in the dark. Besides, my closest neighbor was several miles away. But the ladies said curtains were important. They also presented me with a quilt they had made for our wedding bed. Some of the brethren had come by a week or so before and built us a new bed. My cabin had never looked so good. It reminded me of my mother. I had wanted to cry, but I knew the women would think me weak. I hitched up the horses to the buggy. Then, I brought in several buckets of spring water and filled the tub. I scrubbed off layers and layers of dirt, grime, and dung. I was as clean as a whistle and smelt good, too. Then I dressed in my Sunday best. Nothing too good for my Sarah. I climbed into the buggy and drove the seven miles to her father’s house. I kept thanking God for my good fortune and praying that Sarah hadn’t changed her mind. The ceremony was simple. I was overcome with excitement when I saw Sarah. She looked as beautiful as sunshine on a rainy day. I stuttered through my vows, with a little assistance from my father-in-law. I thought I saw a look of disgust on his face, but it was only for a second, then he was back to his cheerful self. Sarah’s family was warm, caring, and full of laughter. I always felt comfortable in their midst. Some of the more serious brethren believed there was too much joy floating around their house. But Peter Schertz preached that laughter was the holy voices of the angels praising God. Years later, part of the brethren would leave and form a separate church because Peter didn’t preach enough hell and damnation. But on our wedding day there was plenty of joy to go around. I believe that Peter had finally accepted the fact that we loved each other and wanted to get married. He had resisted the notion in the beginning, when I was first courting Sarah. I don’t think he felt that I was good enough for his beautiful daughter, He wanted someone who was better educated and less shy. Someone who didn’t stutter. I think what finally won him over was the kindness that he saw in my heart. He knew I’d never lift a finger to hurt his little girl, and he realized that was more important than all the book learning in the world. After we had feasted on roast beef, mashed potatoes and pie, Sarah and I said our goodbyes. Her goodbyes were long and tearful. This was the first time she would be away from her family and she didn’t realize how difficult it would be until the moment of the departure arrived. When we finally drove off, Sarah kept looking back and waving. And when she could no longer see them, she kept looking anyway. Finally, I stammered out that I loved her and that I hoped she would find her new home to her liking. I told her that I would take good care of her and that she shouldn’t worry. She smiled her gentle smile and kissed me on the cheek. Suddenly, I felt all warm and mushy inside. I wanted to stop the buggy and take her into my arms. But we were crossing a small creek, and it was too dangerous to stop. By the time we reached the other side, the moment had passed. I took her hand in mine and vowed that I would always love her and that I would do anything to make her happy. The rest of the trip home she chattered and sang and laughed, asking me questions about her new home — she had never been there. I visited her at her home. She was eager to know more, and she pestered me with questions that I answered as best I could. I was so excited to show her the house that I left the horse and buggy untethered. Fortunately, the horse didn’t wander off. I scooped her up in my arms and carried her across the threshold. That first night, I felt as if I had died and gone to heaven. May God have mercy on my soul.

III

Sarah, my beautiful Sarah, why do you haunt me in the early morning hours before the coming of the dawn? I hear your voice calling me, begging me to follow you through the doorway of death into the arms of Jesus. I feel your hand as smooth as cornsilk brushing the hair off my forehead and caressing my thick beard as you did so often during our years together. I see your warm smile light up the dark, dank corners of my heart and scare away the shadows that have haunted my soul. You were God’s gift to me. And late at night, I often held your supple body tight against me to keep the demons at bay. I often wonder how a simple farmer like myself, could find so much love in the warm touch of a woman. Sometimes, I would wake up screaming and you would take me in your arms and I’d bury my face in your bosom and the fears would slowly evaporate like morning dew on the leaves of corn. You gave up so much to stay with me. You were smart enough to go to college to become a teacher for the young. I could never read or write or figure as well as you. I loved to hear you read from the Good Book. The sound of your voice opened up the meanings of the scripture and helped me better understand what God intended for our lives. I am a humble farmer, meant to serve the Maker in his many shapes and forms. You are a breath of spring air on a cold winter’s day, blowing through my troubled mind. You freed me from the sins that tormented my soul. A farmer’s life can be tedious. So much work to do. Hard work. Boring work. Backbreaking work. Mindless work. Painful work. And yet you did it all without complaining or ever raising your voice to the children or me. Sarah, my beautiful Sarah, why do you haunt me as I walk through the fields of corn, checking the ears to see when they will be ready for picking? I have missed you so much these twelve years that you have been gone. I’ve thought of remarrying on several occasions but never could bring myself to do it. Don’t get me wrong. Plenty of women showed interest. Widows, mostly, seeking to replace their husbands. My love for you is too strong. I could not get you out of my mind. The girls have moved on with their lives. Married and having children of their own. They come to visit when they can. Only Jeremiah remains by my side, your last gift to me. He has grown into a strong lad and is a tremendous help in my old age. His sisters taught him how to cook so we often cook together. He has your disposition and the kindest heart that you could find in a man. And he works from sunup to sundown. I’ve made sure he has learned how to read and write and figure. He can outfigure his old man. He is very good with numbers. And he loves to read. Every morning after breakfast, he reads the scripture out loud as you used to do. He spends as much time as he can with your father, who is teaching him God’s ways. I hope that someday he becomes a preacher like your father. You would be proud of him. He is the apple of my eye. He has been my pillar of strength during my darkest hours. Good Lord, how I miss you, Sarah. I have been visiting your gravesite more often this past year. I seem to miss you more now than when you first died, if that is possible. You are in my thoughts every moment of every hour. I want to come home to be with you — to hold you again in my arms, to feel your lips on mine. I pray that God will soon grant me my wish. My time here, I think, is short. My body grows weak with sorrow. I do not have the strength of Job to withstand the pain and suffering that your death has caused me. Sarah, my beautiful Sarah, why do you haunt my waking dreams and visit me in my prayers? I know that you will be standing at the gates of heaven waiting with open arms. Forgive me, Sarah, for being so weak. I wish I could be strong like other people who are able to go on with their lives and remarry. I thought the pain of your death would go away. That time would be the big healer. But time has only made my heart grow fonder. I love you more today than the day you died. Sarah, remember when we first were married, and you had so many dreams of things that you wanted to do and places where you wanted to go. Then the children came and our lives were taken over with the raising of a family as well as the daily chores of farming. I am sorry that I was not more attentive to your needs. That I did not find a way for us to travel more. There are so many things that I am sorry for. My jealousy, for one. I worried that someone would steal your heart. I was always watching you for any sign that you loved another. I never said anything to you, but my moodiness was often jealousy in disguise. You tolerated my grouchiness and my temper. I am sorry for any pain I caused you. Sarah, my beautiful Sarah, why do you haunt me? I hear your voice calling: “Come home! Come home!” May God have mercy on my soul!

Notes on Eastman Johnson:

Born in 1824 in Lovell, Maine.

Son of a tavern owner and local postmaster.

Was taught the rudiments of drawing in high school.

When he was 22, he painted portraits of John Quincy Adams, Daniel Webster, and Dolly Madison. He also painted Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Traveled to Europe when he was 25. Studied art in Dusseldorf, Germany.

Spent four years in the Hague, where he studied the Dutch Masters.

He painted some of his best paintings between 1860 and 1880. He became one of America’s best genre painters. He combined h

is European training with American subject matter.

He married at the age of 45 and had one child.

Eastman died on April 5, 1906.