Issue #18

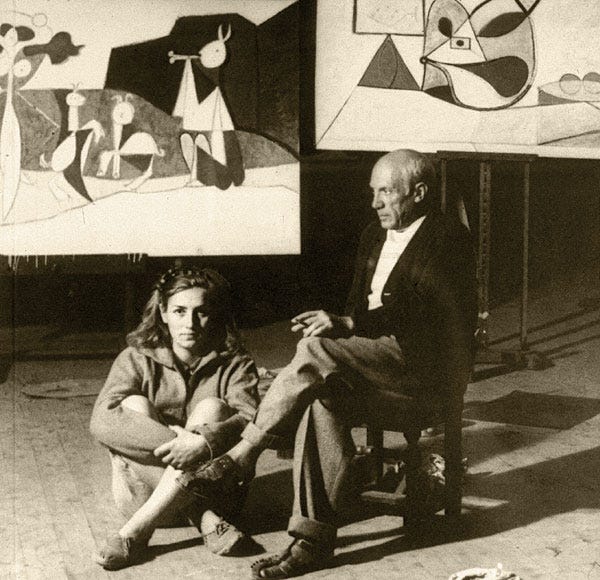

Pablo Picasso and Françoise Gilot in Antibes, 1946 (Photo: Michel Sima)

Francoise

Some ask, "How could you have stayed with such a beast?" Others remark, with awe, "How could you have left such a genius?" And neither understands the true nature of our relationship and the life we shared. At first, it was a game, a challenge, nothing that I took too seriously. I enjoyed the give and take, the sparring like a matador and the bull. Each sees the world through his eyes, his demons. He kissed me once, sudden, unexpected, hard, his lips biting into mine, the pressure of his member, aroused, passionate, like his paint brushes, bristling yet supple. Then he pretended to be shocked when I did not slap him, when I did not yell for help. Instead, I offered myself, a sacrifice on the altar, a muffin to be consumed. And he ran like a child with his hand in the cookie jar, afraid of being too close, afraid of losing himself in my fire. What you and all the others, don't understand is that he was spring to my winter, he was chaos to my structure. My father raised me to be a boy, to follow in his footsteps, to love the practical, the mundane. I rebelled. Pablo offered what my father could not give— freedom, the joy of childhood, anarchy and the fun of living. I bathed in the craziness, the spontaneity, the wild reckless rush towards insanity. Another time, he seduced me into lying naked beside him and then refused to touch me. Claimed that all he wanted was to discover if my body was as beautiful as the one in his imagination. And when I asked whether it was, he only laughed, that deep rumbling, belly-shattering laugh that made me mad. I yelled at him and kicked him. I aimed for his groin, but missed when he stepped aside, my foot glancing off his thigh. I think that one of the things that made our relationship last as long as it did was my independence and defiance. I kept surprising him. He never knew what to expect. I kept him on his toes; I was not the submissive little wife— who waited patiently for her drunken bum of a husband to return home and beat her. I stood up to him from day one. My father, though, until he died believed that Pablo had ruined me— that he had seduced an innocent child, brainwashed me. But I was more my father's child than my father knew. I applied what he taught me to a different arena, a different form of warfare. I controlled Pablo as much if not more than he did me. From the very beginning, I knew what the game was, what the risks were, and I believed that I was strong enough to win. My father had taught me understand the subtleties of the game, and how sometimes you win by appearing to lose. What I did not understand in the beginning—what has taken me years to realize was that Pablo was my father in a different disguise. What I took for spontaneity and anarchy was only the rigidness of my father turned inside out. They were opposite sides of the same coin—cut from the same cloth. Men who in the end behaved like tyrants and if I did not obey, they threw me out. Sure, they enjoyed my independence, and that I was not meek and mild, but only so far—as long as I did not reject them—as long as I eventually gave in, conceded to their wishes, they would tolerate my free spirit— my thinking for myself. They would brag about my intelligence to others. But I had to let them win the final battle— to believe that they had conquered. I had escaped one prison, one set of bars, only to find myself firmly entrenched behind the walls of another. So again, I had to break free, to find my own way, to seek my own path. Yes, I survived living with the great Picasso, and am a stronger woman for having faced the darkness of my fears, for having wrestled with the angel of creativity, for having been consumed by the fires of passion. What does not destroy us can only make us stronger. So when they ask, "How could you leave such a genius," I only smile and say, "It was an honor to have known him."

Notes

Many years ago, I read Life With Picasso, a memoir by Françoise Gilot. Several weeks later, I wrote this poem in response to the book.

Francoise Gilot tells the story of living with Pablo Picasso when he was in his 60s and she was in her 20s. She gave birth to 2 of his four children. Francoise shares stories in the book about Picasso's love life, his friends, and his views on art.

Thanks for reading.

Beautifully done, Harley! What a joy it is to read your work. Thank you.

Thanks for the restack.